1. Introduction

One of the unappetizing aspects of Hadoop to users of traditional HPC is that it is written in Java. Java is not designed to be a high-performance language and, although I can only definitively speak for myself, I suspect that learning it is not a high priority for domain scientists. As it turns out though, Hadoop allows you to write map/reduce code in any language you want using the Hadoop Streaming interface. This is a key feature in making Hadoop more palatable for the scientific community, as it means turning an existing Python or Perl script into a Hadoop job does not require learning Java or derived Hadoop-centric languages like Pig. The following guide illustrates how you can run Hadoop jobs, written entirely in Python, without ever having to mess with any other languages on XSEDE's Gordon resource at SDSC.

Once the basics of running Python-based Hadoop jobs are covered, I will illustrate a more practical example: using Hadoop to parse a variant call format (VCF) file using a VCF parsing library you would install without root privileges on your supercomputing account.

The wordcount example here is on my GitHub account. I've also got implementations of this in Perl and R posted there.

2. Review of Hadoop on HPC

This guide assumes you are familiar with Hadoop and map/reduce at a conceptual level. You should be in good shape after reading the Conceptual Overview of Map/Reduce and Hadoop page I have.

This guide also assumes you understand the basics of running a Hadoop cluster on an HPC resource (supercomputer). This can mean

- using a non-interactive, all-encapsulated job that does the Hadoop cluster setup, job run, and Hadoop cluster teardown all in one job script, as described by the Gordon User Guide's page on Hadoop

- creating a semi-persistent Hadoop cluster using a job script and submitting map/reduce jobs to it by hand, as described by my page on Running Hadoop Clusters on Traditional Supercomputers

For the purposes of keeping the process of specifically running Hadoop

Streaming clear, I will assume we have a Hadoop cluster already spun up

on Gordon using my

semi-persistent Hadoop cluster script

and only provide the relevant hadoop commands involved in

submitting the Hadoop job to this Hadoop cluster. If you want to go the

non-interactive route, I have

a submit script on GitHub

that wraps this example problem into a single non-interactive Gordon job.

3. The Canonical Wordcount Example

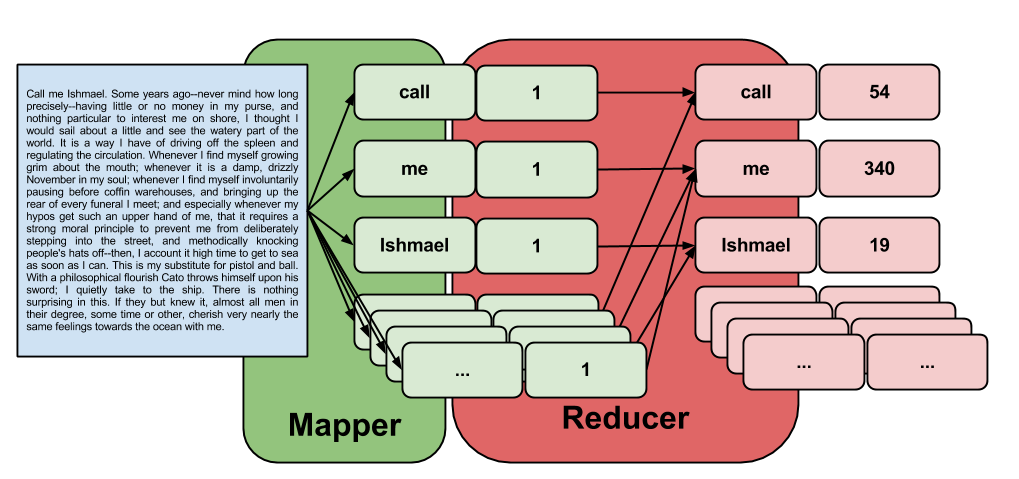

Counting the number of words in a large document is the "hello world" of map/reduce, and it is among the simplest of full map+reduce Hadoop jobs you can run. Recalling that the map step transforms the raw input data into key/value pairs and the reduce step transforms the key/value pairs into your desired output, we can conceptually describe the act of counting words as

- the map step will take the raw text of our document (I will use Herman Melville's classic, Moby Dick) and convert it to key/value pairs. Each key is a word, and all keys (words) will have a value of 1.

- the reduce step will combine all duplicate keys by adding up their values. Since every key (word) has a value of 1, this will reduce our output to a list of unique keys, each with a value corresponding to that key's (word's) count.

With Hadoop Streaming, we need to write a program that acts as the mapper and a program that acts as the reducer. These applications must interface with input/output streams in such a way equivalent to the following series of pipes:

$ cat input.txt | ./mapper.py | sort | ./reducer.py > output.txt

That is, Hadoop Streaming sends raw data to the mapper via stdin, then sends the mapped key/value pairs to the reducer via stdin.

3.1. The Mapper

The mapper, as described above, is quite simple to implement in Python. It will look something like this:

#!/usr/bin/env python

import sys

for line in sys.stdin:

line = line.strip()

keys = line.split()

for key in keys:

value = 1

print( "%s\t%d" % (key, value) )

where

- Hadoop sends a line of text from the input file ("line" being defined by a string of text terminated by a linefeed character,

\n) - Python strips all leading/trailing whitespace (

line.strip() - Python splits that line into a list of individual words along whitespace (

line.split()) - For each word (which will become a key), we assign a value of 1 and then print the key-value pair on a single line, separated by a tab (

\t)

A more detailed explanation of this process can be found in Yahoo's excellent Hadoop Tutorial.

3.2. The Shuffle

A lot happens between the map and reduce steps that is largely transparent to the developer. In brief, the output of the mappers is transformed and distributed to the reducers (termed the shuffle step) in such a way that

- All key/value pairs are sorted before being presented to the reducer function

- All key/value pairs sharing the same key are sent to the same reducer

These two points are important because

- As you read in key/value pairs, if you encounter a key that is different from the last key you processed, you know that that previous key will never appear again

- If your keys are all the same, you will only use one reducer and gain no parallelization. You should come up with a more unique key if this happens!

3.3. The Reducer

The output from our mapper step will go to the reducer step sorted. Thus, we can loop over all input key/pairs and apply the following logic:

If this key is the same as the previous key,

add this key's value to our running total.

Otherwise,

print out the previous key's name and the running total,

reset our running total to 0,

add this key's value to the running total, and

"this key" is now considered the "previous key"

Translating this into Python and adding a little extra code to tighten up the logic, we get

#!/usr/bin/env python

import sys

last_key = None

running_total = 0

for input_line in sys.stdin:

input_line = input_line.strip()

this_key, value = input_line.split("\t", 1)

value = int(value)

if last_key == this_key:

running_total += value

else:

if last_key:

print( "%s\t%d" % (last_key, running_total) )

running_total = value

last_key = this_key

if last_key == this_key:

print( "%s\t%d" % (last_key, running_total) )

3.4. Running the Hadoop Job

If we name the mapper script mapper.py and the reducing script

reducer.py, we would first want to download the input data (Moby

Dick) and load it into HDFS. I purposely am renaming the copy stored in HDFS

to mobydick.txt instead of the original pg2701.txt to

highlight the location of the file:

$ wget http://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/2701/pg2701.txt

$ hadoop dfs -mkdir wordcount

$ hadoop dfs -copyFromLocal ./pg2701.txt wordcount/mobydick.txt

You can verify that the file was loaded properly:

$ hadoop dfs -ls wordcount/mobydick.txt

Found 1 items

-rw-r--r-- 2 glock supergroup 1257260 2013-07-17 13:24 /user/glock/wordcount/mobydick.txt

Before submitting the Hadoop job, you should make sure your mapper and reducer scripts actually work. This is just a matter of running them through pipes on a little bit of sample data (e.g., the first 1000 lines of Moby Dick):

$ head -n1000 pg2701.txt | ./mapper.py | sort | ./reducer.py

...

young 4

your 16

yourself 3

zephyr 1

Once you know the mapper/reducer scripts work without errors, we can plug

them into Hadoop. We accomplish this by running the Hadoop Streaming jar file

as our Hadoop job. This hadoop-streaming-X.Y.Z.jar file comes

with the standard Apache Hadoop distribution and should be in

$HADOOP_HOME/contrib/streaming

where $HADOOP_HOME is the base directory of your Hadoop installation

and X.Y.Z is the version of Hadoop you are running. On Gordon

the location is /opt/hadoop/contrib/streaming/hadoop-streaming-1.0.3.jar,

so our actual job launch command would look like

$ hadoop \

jar /opt/hadoop/contrib/streaming/hadoop-streaming-1.0.3.jar \

-mapper "python $PWD/mapper.py" \

-reducer "python $PWD/reducer.py" \

-input "wordcount/mobydick.txt" \

-output "wordcount/output"

packageJobJar: [/scratch/glock/819550.gordon-fe2.local/hadoop-glock/data/hadoop-unjar4721749961014550860/] [] /tmp/streamjob7385577774459124859.jar tmpDir=null

13/07/17 19:26:16 INFO util.NativeCodeLoader: Loaded the native-hadoop library

13/07/17 19:26:16 WARN snappy.LoadSnappy: Snappy native library not loaded

13/07/17 19:26:16 INFO mapred.FileInputFormat: Total input paths to process : 1

13/07/17 19:26:16 INFO streaming.StreamJob: getLocalDirs(): [/scratch/glock/819550.gordon-fe2.local/hadoop-glock/data/mapred/local]

13/07/17 19:26:16 INFO streaming.StreamJob: Running job: job_201307171926_0001

13/07/17 19:26:16 INFO streaming.StreamJob: To kill this job, run:

13/07/17 19:26:16 INFO streaming.StreamJob: /opt/hadoop/libexec/../bin/hadoop job -Dmapred.job.tracker=gcn-13-34.ibnet0:54311 -kill job_201307171926_0001

13/07/17 19:26:16 INFO streaming.StreamJob: Tracking URL: http://gcn-13-34.ibnet0:50030/jobdetails.jsp?jobid=job_201307171926_0001

And at this point, the job is running. That "tracking URL" is a bit

deceptive in that you probably won't be able to access it. Fortunately, there

is a command-line interface for monitoring Hadoop jobs that is somewhat similar

to qstat. Noting the Hadoop jobid (highlighted above), you can do:

$ hadoop -status job_201307171926_0001

Job: job_201307171926_0001

file: hdfs://gcn-13-34.ibnet0:54310/scratch/glock/819550.gordon-fe2.local/hadoop-glock/data/mapred/staging/glock/.staging/job_201307171926_0001/job.xml

tracking URL: http://gcn-13-34.ibnet0:50030/jobdetails.jsp?jobid=job_201307171926_0001

map() completion: 1.0

reduce() completion: 1.0

Counters: 30

Job Counters

Launched reduce tasks=1

SLOTS_MILLIS_MAPS=16037

Total time spent by all reduces waiting after reserving slots (ms)=0

Total time spent by all maps waiting after reserving slots (ms)=0

Launched map tasks=2

Data-local map tasks=2

...

Since the hadoop streaming job runs in the foreground, you will have to use another terminal (with HADOOP_CONF_DIR properly exported) to check on the job while it runs. However, you can also review the job metrics after the job has finished. In the example highlighted above, we can see that the job only used one reduce task and two map tasks despite the cluster having more than two nodes.

3.5. Adjusting Parallelism

Unlike with a traditional HPC job, the level of parallelism a Hadoop job is not necessarily the full size of your compute resource. The number of map tasks is ultimately determined by the nature of your input data due to how HDFS distributes chunks of data to your mappers. You can "suggest" a number of mappers when you submit the job though. Doing so is a matter of applying the change highlighted:

$ hadoop jar /opt/hadoop/contrib/streaming/hadoop-streaming-1.0.3.jar \

-D mapred.map.tasks=4 \

-mapper "python $PWD/mapper.py" \

-reducer "python $PWD/reducer.py" \

-input wordcount/mobydick.txt \

-output wordcount/output

...

$ hadoop -status job_201307172000_0001

...

Job Counters

Launched reduce tasks=1

SLOTS_MILLIS_MAPS=24049

Total time spent by all reduces waiting after reserving slots (ms)=0

Total time spent by all maps waiting after reserving slots (ms)=0

Rack-local map tasks=1

Launched map tasks=4

Data-local map tasks=3

Similarly, you can add -D mapred.reduce.tasks=4 to suggest the

number of reducers. The reducer count is a little more flexible, and you can

set it to zero if you just want to apply a mapper to a large file.

With all this being said, the fact that Hadoop defaults to only two mappers says something about the problem we're trying to solve--that is, this entire example is actually very stupid. While it illustrates the concepts quite neatly, counting words in a 1.2 MB file is a waste of time if done through Hadoop because, by default, Hadoop assigns chunks to mappers in increments of 64 MB. Hadoop is meant to handle multi-gigabyte files, and actually getting Hadoop streaming to do something useful for your research often requires a bit more knowledge than what I've presented above.

To fill in these gaps, the next part of this tutorial, Parsing VCF Files with Hadoop Streaming, shows how I applied Hadoop to solve a real-world problem involving Python, some exotic Python libraries, and some not-completely-uniform files.

This document was developed with support from the National Science Foundation (NSF) under Grant No. 0910812 to Indiana University for "FutureGrid: An Experimental, High-Performance Grid Test-bed." Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the NSF.