The Programmable Real-time Unit (PRU)

The most unique feature of BeagleBone (and its underlying TI Sitara SoC) are its PRUs which are realtime microcontrollers that are nicely integrated with the ARM core. You have two options to program the PRUs:

- Using TI's Code Composer Studio (CCS). This is overly complicated if all you want to do is treat the PRUs as a part of an embedded Linux system though.

- Program the PRUs from within Linux on the BeagleBone itself. This is the easier approach if you are familiar with Linux but not programming ARM directly.

Hereafter we're only considering the second option, and the BeagleBone OS ships

with the necessary tools to make this work already in /usr/lib/ti/pru-software-support-package.

In this mode, the PRUs are exposed to Linux as remote processors which have

a pretty simple API with which you can

- Load "firmware" (compiled code) into a PRU

- Start execution on a PRU

- Stop execution on a PRU

These remote processors can be accessed in /sys/class/remoteproc which, on

BeagleBone Black, contains:

remoteproc0- the ARM Cortex-M3 processor on the BeagleBone. This isn't documented very well because it is preloaded with code that handles power management on the board. If you don't care about power management, I assume you could overwrite its firmware and do as you please with it.remoteproc1- PRU0, called4a334000.pruremoteproc2- PRU1, called4a338000.pru

Basic usage

To load compiled firmware into a PRU, first copy the compiled code into

/lib/firmware:

cp myfirmware.bin /lib/firmware/myfirmware.bin

Linux will read the contents of /sys/class/remoteproc/remoteproc1/firmware and

look for a file in /lib/firmware with that name to load into PRU0 when it is

started, so we have to tell it the name of this new firmware:

echo "myfirmware.bin" > /sys/class/remoteproc/remoteproc1/firmware

Then tell the PRU to boot up:

echo "start" > /sys/class/remoteproc/remoteproc1/state

TI's documentation for all this can be found in the RemoteProc and RPMsg section of the Processor SDK Linux Software Developer's Guide.

Hello world example

A minimal working example of a PRU firmware source is as follows:

#include <stdint.h>

#include <rsc_types.h> /* provides struct resource_table */

#define CYCLES_PER_SECOND 200000000 /* PRU has 200 MHz clock */

#define P9_31 (1 << 0) /* R30 at 0x1 = pru1_pru0_pru_r30_0 = ball A13 = P9_31 */

volatile register uint32_t __R30; /* output register for PRU */

void main(void) {

while (1) {

__R30 |= P9_31; /* set first bit in register 30 */

__delay_cycles(CYCLES_PER_SECOND / 4); /* wait 0.5 seconds */

__R30 &= ~P9_31; /* unset first bit in register 30 */

__delay_cycles(CYCLES_PER_SECOND / 4); /* wait 0.5 seconds */

}

}

/* required by PRU */

#pragma DATA_SECTION(pru_remoteproc_ResourceTable, ".resource_table")

#pragma RETAIN(pru_remoteproc_ResourceTable)

struct my_resource_table {

struct resource_table base;

uint32_t offset[1];

} pru_remoteproc_ResourceTable = { 1, 0, 0, 0, 0 };

The PRU can directly toggle a subset of the BeagleBone's GPIO pins in a single

cycle by manipulating bits in register #30. That register is exposed in

C as __R30, so modifying that register's contents directly triggers a change

in one or more GPIO pin states. See the PRU Optimizing C/C++ Compiler User

Guide Section 5.7.2 for more info.

The first (least significant) bit in __R30 controls pin 31 on header P9, so

flipping that bit on and off will make that pin go high and low. Since the PRUs

run at 200 MHz and can complete one operation per cycle, this means a pin can be

flipped on or off in 5 ns. That's fast!

The resource table junk at the bottom has to be in any code loaded into the PRU. This table is used to configure things like its buffers for communicating with the ARM host and handling interrupts.

Compiling PRU firmware

Compiling this code for the PRU can be done with either the official TI

toolchain (the clpru compiler and lnkpru linker) or the GCC frontend for

the PRU. I haven't tried GCC yet, so let's stick with the TI toolchain. The

minimal makefile for the above looks like this:

PRU_SWPKG = /usr/lib/ti/pru-software-support-package

CC = clpru

LD = lnkpru

CFLAGS = --include_path=$(PRU_SWPKG)/include \

--include_path=$(PRU_SWPKG)/include/am335x

LDFLAGS = $(PRU_SWPKG)/labs/lab_2/AM335x_PRU.cmd

all: am335x-pru0-fw

hello-pru0.o: hello-pru0.c

$(CC) $(CFLAGS) $^ --output_file $@

am335x-pru0-fw: hello-pru0.o

$(LD) $(LDFLAGS) $^ -o $@

This will do the following:

$ clpru --include_path=/usr/lib/ti/pru-software-support-package/include \

--include_path=/usr/lib/ti/pru-software-support-package/include/am335x \

hello-pru0.c \

--output_file hello-pru0.o

$ lnkpru /usr/lib/ti/pru-software-support-package/labs/lab_2/AM335x_PRU.cmd \

hello-pru0.o \

-o am335x-pru0-fw

This compiles the C source into an object, then links the object with a special

linker command file (AM335x_PRU.cmd) to create a complete firmware that the

PRU can execute. This firmware is called am335x-pru0-fw.

Configuring GPIO pins

In the above example, we want to allow the PRU to control P9_31 through its

__R30 register. To do that, we have to make sure that P9_31 is configured

to expose its PRU output mode functionality:

$ config-pin P9_31 pruout

Current mode for P9_31 is: pruout

See the Set GPIO pin modes section for more info.

Launching code

You cannot load firmware onto a PRU while it's running, so check its state:

$ cat /sys/class/remoteproc/remoteproc1/state

offline

If it's anything but offline, stop it using

$ echo stop > /sys/class/remoteproc/remoteproc1/state

Then copy our firmware into the directory where Linux will look for new firmware to load:

$ cp am335x-pru0-fw /lib/firmware/am335x-pru0-fw

Then make sure that Linux will be looking for a file with this name in

/lib/firmware:

$ cat /sys/class/remoteproc/remoteproc1/firmware

am335x-pru0-fw

This tells us that when we start the PRU, it will indeed look for a file called

am335x-pru0-fw in /lib/firmware. Now just start the PRU:

$ echo start > /sys/class/remoteproc/remoteproc1/state

And verify that it's running by either looking at the LED to confirm that it blinks on and off at quarter-second intervals:

Or ask Linux to check on its state:

$ cat /sys/class/remoteproc/remoteproc1/state

running

If the state is still offline, there was a problem. Check journalctl for

errors:

$ journalctl --system --priority err

...

Jun 08 22:20:49 beaglebone kernel: remoteproc remoteproc1: header-less resource table

Jun 08 22:20:49 beaglebone kernel: remoteproc remoteproc1: Boot failed: -22

In the above example, I tried to boot code that was missing the resource table data structure.

You can download the above minimum viable product from my BeagleBone repository on GitHub.

PRU GPIO

The PRU has direct access to a subset of the GPIOs available on the BeagleBone

Black through the __R30 and __R31 registers. Here's a handy dandy table

that maps the lower bits in these registers to physical header pins on

BeagleBone Black:

| bit | pru0's R30 | pru1's R30 | pru0's R31 | pru1's R31 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | P9_31 | P8_45 | P9_31 | P8_45 |

| 1 | P9_29 | P8_46 | P9_29 | P8_46 |

| 2 | P9_30 | P8_43 | P9_30 | P8_43 |

| 3 | P9_28 | P8_44 | P9_28 | P8_44 |

| 4 | P9_42B | P8_41 | P9_42B | P8_41 |

| 5 | P9_27 | P8_42 | P9_27 | P8_42 |

| 6 | P9_41B | P8_39 | P9_41B | P8_39 |

| 7 | P9_25 | P8_40 | P9_25 | P8_40 |

| 8 | P8_27 | P8_27 | ||

| 9 | P8_29 | P8_29 | ||

| 10 | P8_28 | P8_28 | ||

| 11 | P8_30 | P8_30 | ||

| 12 | P8_21 | P8_21 | ||

| 13 | P8_20 | P8_20 | ||

| 14 | P8_12 | P9_16 | ||

| 15 | P8_11 | P8_15 | ||

| 16 | P9_24/P9_41A | P8_26 |

Direct General Purpose Output

If you want to run code on pru0 and turn on an LED using the 0th bit of __R30

(as we did for our hello world example), the table above says you should plug

your LED into P9_31. To run the same code on pru1 though, you'd have to plug

your LED into P8_45. It's a little annoying that the same firmware cannot run

on both PRUs without modification, but that's the way the BeagleBone Black is

wired up.

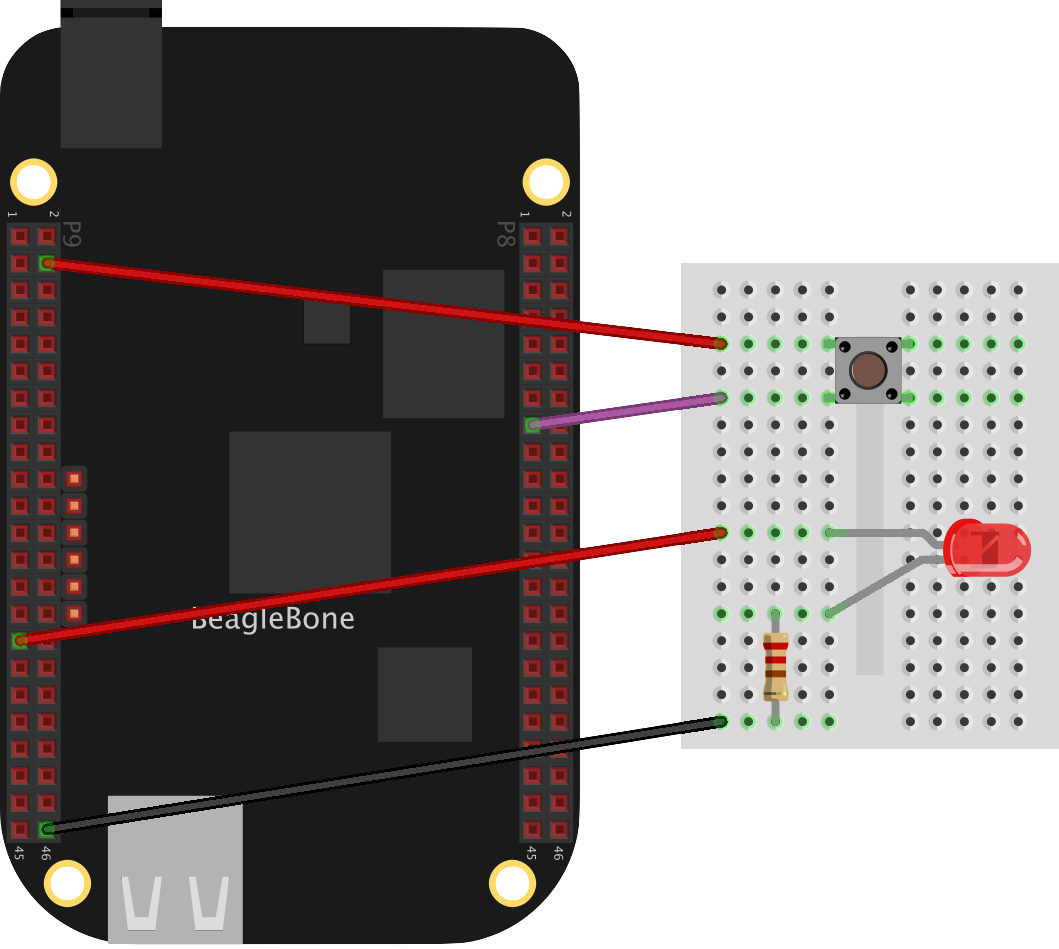

Direct General Purpose Input

In the hello world example above, we saw that we can turn on an LED connected

to P9_31 by flipping the first bit in __R30:

__R30 |= 1;

You can also read input directly from the PRU by reading values from __R31.

Consider the simplest case where you have the following connected in series:

3.3V --> push button --> P8_15 header

If you were to read the 15th bit of __R31 like this:

input_bit = __R31 & (1 << 15);

You would see that input_bit = 1 when the button was pressed and 0 otherwise.

It's not too much of a stretch to combine this logic with our blinky LED from

the hello world example and use the PRU to turn on an LED while the button is

pressed. Wire it up something like this:

And the remainder is pretty simple. Here's a fully working example:

#include <stdint.h>

#include <rsc_types.h> /* provides struct resource_table */

#define P9_31 (1 << 0)

#define P8_15 (1 << 15)

volatile register uint32_t __R30, __R31;

void main(void) {

while (1) {

if (__R31 & P8_15) /* if button is pressed */

__R30 |= P9_31; /* set bit */

else

__R30 &= ~P9_31; /* remove bit */

}

}

/* required by PRU */

#pragma DATA_SECTION(pru_remoteproc_ResourceTable, ".resource_table")

#pragma RETAIN(pru_remoteproc_ResourceTable)

struct my_resource_table {

struct resource_table base;

uint32_t offset[1];

} pru_remoteproc_ResourceTable = { 1, 0, 0, 0, 0 };

This checks to see if header P8_15 is high (__R31 & P8_15) which would

indicate that the button is pressed and P8_15 is connected to the 3.3V

line. If it is, it turns on the LED-resistor series connected to P9_31,

and if not, it turns it off. Be sure to configure your pins correctly before

trying this code!

config-pin p8_15 pruin

config-pin p9_31 pruout

This example is a bit trivial because the same would happen if there was no

BeagleBone at all and you just had a switch in series with 3.3V, a resistor,

and the LED. To actually have the PRU apply some logic to the LED, I took it

a step further and made the LED blink while the button was pressed. My main()

looks like this:

#define SET_BIT(reg, bit) (reg) |= (bit)

#define REMOVE_BIT(reg, bit) (reg) &= ~(bit)

#define IS_SET(reg, bit) (reg) & (bit)

void main(void) {

uint8_t led_state = 0;

REMOVE_BIT(__R30, P9_31); /* initial LED state is off */

while (1) {

/* if button is pressed */

if (IS_SET(__R31, P8_15)) {

/* alternate between LED on and off */

if (led_state) {

REMOVE_BIT(__R30, P9_31);

led_state = 0;

}

else {

SET_BIT(__R30, P9_31);

led_state = 1;

}

}

else {

/* if button not pressed, make sure LED is off */

REMOVE_BIT(__R30, P9_31);

}

/* repeat this check every 0.1 seconds */

__delay_cycles(CYCLES_PER_SECOND / 10);

}

}

I also added the SET_BIT, REMOVE_BIT, and IS_SET macros for clarity this

time.

You can see the full source code for these button examples in my BeagleBone PRU GitHub repository.

PRU UART

Each PRU has its own UART which are pretty similar to the TI16C550C, and this is one of the easiest ways to communicate with the PRU without having to interface with the rest of the BeagleBone host CPU. For example, you just connect a USB to TTL serial cable as

- Green to header P9, pin 17

- White to header P9, pin 18

- Black to ground

which should look something like this:

Then configure P9 pin 17 and 18 for PRU UART (e.g., config-pin p9_17 pru_uart),

plug the USB end of the TTL cable into a Mac or Linux system, and use something

like cu or screen to connect in:

$ screen /dev/tty.usbserial-0001 $((12*9600))

Figuring out how to make the UART talk is a matter of digging through

- The AM335x Technical Reference Manual, Section 4.4.4 on the UART

- The TI16C550C data sheet

- The pru_uart.h header that comes with the PRU Software Support Package

The pru_uart.h header gives you the CT_UART identifier that provides

convenient access to all the UART registers required to interact with the

UART. Let's walk through that process for the simplest possible case.

Initializing the PRU UART

When the PRU is started, the UART is reset into a default configuration (see Table 7-2 in the TI16C550C data sheet. We have to set a few parameters like baud rate and mode of operation like this:

#include <pru_uart.h> /* provides CT_UART */

void uart_init(void)

{

CT_UART.DLL = 104; /* divisor latch low */

CT_UART.DLH = 0; /* divisor latch high - aka DLM*/

CT_UART.MDR_bit.OSM_SEL = 0; /* 16x oversampling */

CT_UART.LCR_bit.WLS = 3; /* word length select; 0b11 = 8 bits */

CT_UART.FCR_bit.FIFOEN = 1; /* FIFO enable */

CT_UART.FCR_bit.RXCLR = 1; /* receiver FIFO reset */

CT_UART.FCR_bit.TXCLR = 1; /* transmitter FIFO reset */

CT_UART.PWREMU_MGMT_bit.URRST = 1; /* enable transmitter */

CT_UART.PWREMU_MGMT_bit.UTRST = 1; /* enable receiver */

}

The first three register bits (DLL, DLH, and the OSM_SEL bit in MDR)

tell us we want to use 115200 baud (12 &215; 9600). Knowing that our UART is hooked

up to a 192 MHz clock, the baud rate is just

clock * DLL * oversample

or

192,000,000 / 104 / 16 = 115384

which is pretty darned close to 115200. We also set the word length select bit

in the line control register (LCR) to configure the uart for 8-bit word

lengths since this is the standard (WLS = 0b11 means use an 8-bit word length).

This is also where we'd set our desired number of stop bits and disable parity,

but those are the default settings on this UART.

The FCR register settings mean we want to use the UART's built-in 16-byte FIFO

buffer and ready it for use. This allows us to buffer up to 16 characters

before having to check status registers to see if we can send more data.

Finally, manipulating the PWREMU_MGMT register is how we turn on the UART.

Sending Data

To send data over the UART (i.e., make the PRU talk), you just fill up the

FIFO by writing bytes to the transmitter hold register (THR). This is a

16-byte FIFO that will asynchronously feed the transmitter shift register

(TSR) which is where your bytes are turned into UART frames and sent over

the wire. The process for sending data is:

- Make sure the transmitter hold and shift registers are empty--if they are not, you risk overflowing.

- Write one byte at a time to the

THRup to 16 bytes, which is our FIFO size. - Wait until the transmitter hold and shift registers are empty again, indicating that your bytes have been sent over the wire.

- Repeat until you've sent all your data.

You check the state of the transmitter hold and shift registers (step 1 and 3)

by checking the transmitter empty (TEMT) bit in the line status register

(LSR).

The code to do this is as follows:

#define FIFO_SIZE 16

void uart_tx(char *s)

{

uint8_t index = 0;

do {

uint8_t count = 0;

while (!CT_UART.LSR_bit.TEMT) /* step 1 and 3: loop until TEMT is set */

;

while (s[index] != '\0' && count < FIFO_SIZE) {

CT_UART.THR = s[index]; /* step 2 */

index++;

count++;

}

} while (s[index] != '\0'); /* step 3 */

}

This mode of operation (send then wait) is called polling mode because we are

continually polling the TEMT bit to see if the send is complete yet. The

UART also supports an interrupt mode which I haven't tried using yet.

Receiving Data

Receiving data is a simple matter of copying bytes out of the receive buffer

register (RBR) whenever there is data ready there. You can check to see if

data is ready by checking the data ready bit in the line status register.

In code,

void uart_rx(char *buf, uint32_t size) {

uint32_t i;

for (i = 0; i < size - 1; i++) {

while (!CT_UART.LSR_bit.DR) /* !data ready? */

;

buf[i] = CT_UART.RBR_bit.DATA;

if (buf[i] == '\r')

break;

}

buf[i] = '\0';

}

A challenge with polling mode is that we don't know when to stop checking for

incoming data and switch back to sending outgoing data, and we only have one

PRU core to poll for both send and receives. In the above code, we check for

the carriage return character (\r) to denote an end of transmission. We

also treat the transmission as over when it fills up the buffer we allocated

(buf) since we don't want to overflow it.

Tying it all together

Using the uart_init(), uart_tx(), and uart_rx(), we have everything we

need to run a PRU application that sends and receives data over serial:

#define BUF_SIZE 40

void main(void)

{

char buf[BUF_SIZE] = { '\0' };

uint8_t done = 0;

uart_init();

while (!done) {

uart_tx("\n\rEnter some characters: ");

uart_rx(buf, BUF_SIZE);

uart_tx("\n\rYou entered: ");

uart_tx(buf);

}

}

This is pretty limited, but it's enough to do basic I/O to and from the PRU that's a little more expressive than turning an LED on or off. You can download the fully working example from my BeagleBone PRU GitHub repository.

PRU Interrupt Controller

Broadly speaking, interrupts are a way to let a computer know that something important has happened and that it should be dealt with immediately. When you click a link on this page, your mouse generates an interrupt. The code that gets executed on this interrupt is its interrupt handler; for the mouse click, this might mean figuring out what link your cursor was hovering over when you clicked and sending your browser there.

Interrupts exist so that a CPU core doesn't have to spend all its time checking the status of your mouse button to see if it is clicked. Considering that every keyboard button, every mouse button, and every network packet that arrives generate an interrupt, you can understand why using the CPU to check for new interrupts, deciding how important they are, and executing interrupt handlers becomes very expensive.

The interrupt controller exists to help mitigate this challenge. Like an administrative assistant, it receives interrupts from peripherals and does the work of evaluating how important each one is and the order in which they must be handled by the operating system. This means the operating system only needs to ask the interrupt controller what's next on the list of interrupts to be handled rather than check all of them and rank them itself.

Each PRU has its own interrupt handler which does exactly this--receive and prioritize various events that may have to be dealt with.

Specific to the PRU's interrupt handler documentation, there is a bit of nomenclature:

- A peripheral is something that can talk to the PRU.

- It can be something like a push button attached to a GPIO pin.

- It can also be something built-in like a DMA controller.

- Peripherals can generate events.

- An event describes the occurrence of a certain action.

- There are 64 defined events on the PRU.

- Events are hard-coded to specific peripherals.

- Events sound a lot like OS signals in that they are predefined but can be intercepted or ignored.

- Events map to "channels."

- A channel groups together multiple events.

- One channel can have zero, one, or multiple events mapped to it.

- The PRU interrupt controller has ten channels.

- Channels map to "host interrupts."

- A host interrupt collects events from channels.

- One host interrupt can have zero, one, or multiple channels mapped to it.

- The PRU interrupt controller supports ten host interupts.

- Host interrupt 0 and 1 are magical.

- the 30th bit in

__R31is mapped to host interrupt 0 - the 31st bit in

__R31is mapped to host interrupt 1

- the 30th bit in

A diagram showing this relationship would be handy to have here.

Why have events, channels, and host interrupts?

- Events can be enabled or disabled, so if you don't care if a certain peripheral does something, you can just disable its events and never have to deal with it.

- Channels let you prioritize events. Channel 0 has the highest priority, so if an event needs to be dealt with immediately, you would map it to channel 0. Less-important events can be mapped to higher channels.

- Host interrupts let you route a channel to a particular action to take.

This mapping of events, channels, and host interrupts is all handled through the interrupt controller on the PRU. To enable/disable events, establish mappings between events, channels, and host interrupts, and configure other bits of how events should translate into actions, you twiddle the bits in a set of 63 registers exposed by this interrupt controller.

For example, the general setup for the interrupt controller involves:

- Enabling an event. This involves writing its event number to the system

event enable indexed set register (

EISR). - Mapping an event to a channel. This involves setting a four-bit range

within one of the 32-bit channel map registers (

CMR) to the appropriate channel. These channel map registers have four-bit ranges for all 64 system events. - Mapping a host interrupt to a channel. Similar to step 2 above, this

involves setting a four-bit range within one of the 32-bit host map

registers (

HMR) to the appropriate host interrupt. - Enabling a host interrupt. This involves writing the host interrupt

number to the host interrupt enable indexed set register (

HIEISR). The behavior is analogous to theEISRregister. - Turning on the interrupt controller. This is done by writing a 1 to the

global host interrupt enable register (

GER).